Cristea Nian Zhao

My home is on a Swamp

(the Practice of Belonging and Un-belonging)

My home is on a Swamp (the Practice of Belonging and Un-belonging) is a research-based project that combines video, still images and a personal written narrative. Challenging the notion of ‘home’ and ‘belongingness’, Cristea Zhao’s provokes a psychological process of reclaiming the past, while searching for what is not there and calling for those who cannot answer.

This project culminates with a performance on live streamed through our Youtube Channel.

I respectfully acknowledge the Boonwurrung and Wurundjeri people of the Kulin Nation, who are the Traditional Owners of the land on which I live and developed this work. I pay my respect to their Elders, past, present and emerging.

1

… he dreamt the exact same dream, in hairsbreadth detail, over and over again, he dreamt that his wanderings had come to an end—and he now sees before him some kind of huge clock, or wheel, or some kind of rotating workshop, after waking he is never able to identify it with certainty, and in any event he is in front of something like this, or some sort of grouping of these things—he steps into the clock, or the wheel, or the workshop, he stands in the middle, and in that unspeakable fatigue in which he has spent his entire life, … he lies down so that he can finally sleep like an animal exhausted onto death, and the dream continually repeats itself, … ¹

2

I recently found out that my home was on a swamp.

3

Constantly relocating since an early age and having multiple experiences added up to my identities as a migrant and an immigrant, I have lost my grip on defining where home is. The complexity doesn’t really reveal itself when I was younger, considering the early-life experience was still reachable in my archive of memories as a significant reference, and as a child, apparently, I was very much indulgently unaware of what is to come ahead of me—I might have sensed it, but I didn’t know; most importantly, I had the privilege of carefreeness, though the privilege didn’t last long. Let me introduce you to my method of locating where you belong when you feel you do not belong where you are.

4

It wouldn’t take long to get there—it would be exactly one hour on a train, 23 minutes on a bus, and 15 minutes on foot. You’d have to pass through a cemetery with an artificial landscape, almost sterile looking. It was established the same year I was born; what a beautiful coincidence, I rest here with thirty thousand souls. Crossing a two-way road you’d see my home. Two gum trees whisper to you; one dead, the other one alive. A handful of swamp wattles are strewn across the field. Taking a walk deep into it, your feet sink into the ground, spear grass floods over you; dragonflies float against the wind; wild ducks peck on the ripples. If you’re lucky enough, you’d also see two black swans with their babies following behind.

5

When I say that the object of my grief is less the village, the mother, or the lover that I miss here and now than the blurred representation that I keep and put together in the darkroom of what thus becomes my psychic tomb, this at once locates my ill-being in the imagination. ²

6

Aren’t the meanings and the usage of the word home fascinating? So flexible that it almost appears as a paradox of presence and spatiality. For example, I can say my home is in Fitzroy but also my home is thousands of miles away in a place you have never been. However, even if I ever hop on a plane and fly back home, I would have no idea which home to go back to; and besides, I would have no home to stay in either. The inclusive usage of this word is coherent and consistent with its concept, indicating a great deal of tolerance and compassion. Home doesn’t require our presence for itself to be tenable; sadly, for many, home doesn’t even obtain its own presence.

A migrant’s home never asks for much. The narrative of absence and loss inherently dwells in it. International or national/regional, voluntary or involuntary, permanent or temporary, no matter which force driven, migration experience consistently resides in the structure of melancholia as a failed mourning. Losing taste buds, losing belongings, losing property, losing name, losing language, losing identity. The detachment from homeland is done and fixed, followed by the attempt at assimilation (or racialised incorporation in some cases) but that could never be fully accomplished. The never-ending endeavour crystallizes into an interminable reinstatement, yearning to comprehend what is lost and to recover what is lost. Home thus shattered into an unstable representation that I can only reclaim internally and momentarily. Every single day, I bear the weight of my own desire and I survive in it.

7

You’d be standing on the land that used to be a swamp; before that it was part of the sea for 2000 years. I come here all the time—you’d find me deep inside the dense blanket of grass. The first thing colonists did was a survey that divided it into 18 pieces. They referred to the land as Allotments on the Long Beach, and the first sale was made in an auction room on Collins Street; then little channels were made across it, bearing the waters of the Dandenong and Eumemmerring Creeks and flowing into the Mordialloc and Kananook Creeks, the only two natural water channels leading to Port Phillip Bay. That was when the call of the kookaburra echoed less in my dreams. In the end the swamp was drained through a 30-foot-wide cut into Port Phillip Bay, heavy storms rushed over immediately after the initial operation. Flood water at Carrum burst through the bridge embankment over the freshly cut river again and again. The tides widened the outfall from 30 feet to 300 feet. Years of floods and storms followed. Various trusts and committees were founded, abolished, and then founded again. Further drainage and reclamation works were commissioned and carried out intermittently for more than a century.³

People did say it was an ‘earthly paradise of thousands of years’.⁴ What you’d see now is not what it used to be.

8

I tried to list all the places that temporarily carried my presence. During this process I realise it is impractical to separate episodic memory from the association for home.

I could hardly picture those living quarters where I spent my brief childhood, but I do remember the last time I stood on the doorstep of that apartment. Central heating blew onto my face when the door was opened. I was unable to cross the threshold; it had already become someone else’s home. The winter in the north-west part of China is icier than the south. I also remember holding my father’s hand on a late summer night, a couple days before I started school. He said this is going to be your new home and I looked up at his eyes, thinking I could have it all. Of course, too many other fragments of memory regarding home; among them there was also a chilly night in late November outside the empty Jade Buddha Temple where my mother and I tried to figure out which direction the crack in the chalk circle should face—it ought to be pointing to where the dead rest—that was for burning paper money on a death anniversary of her father.

9

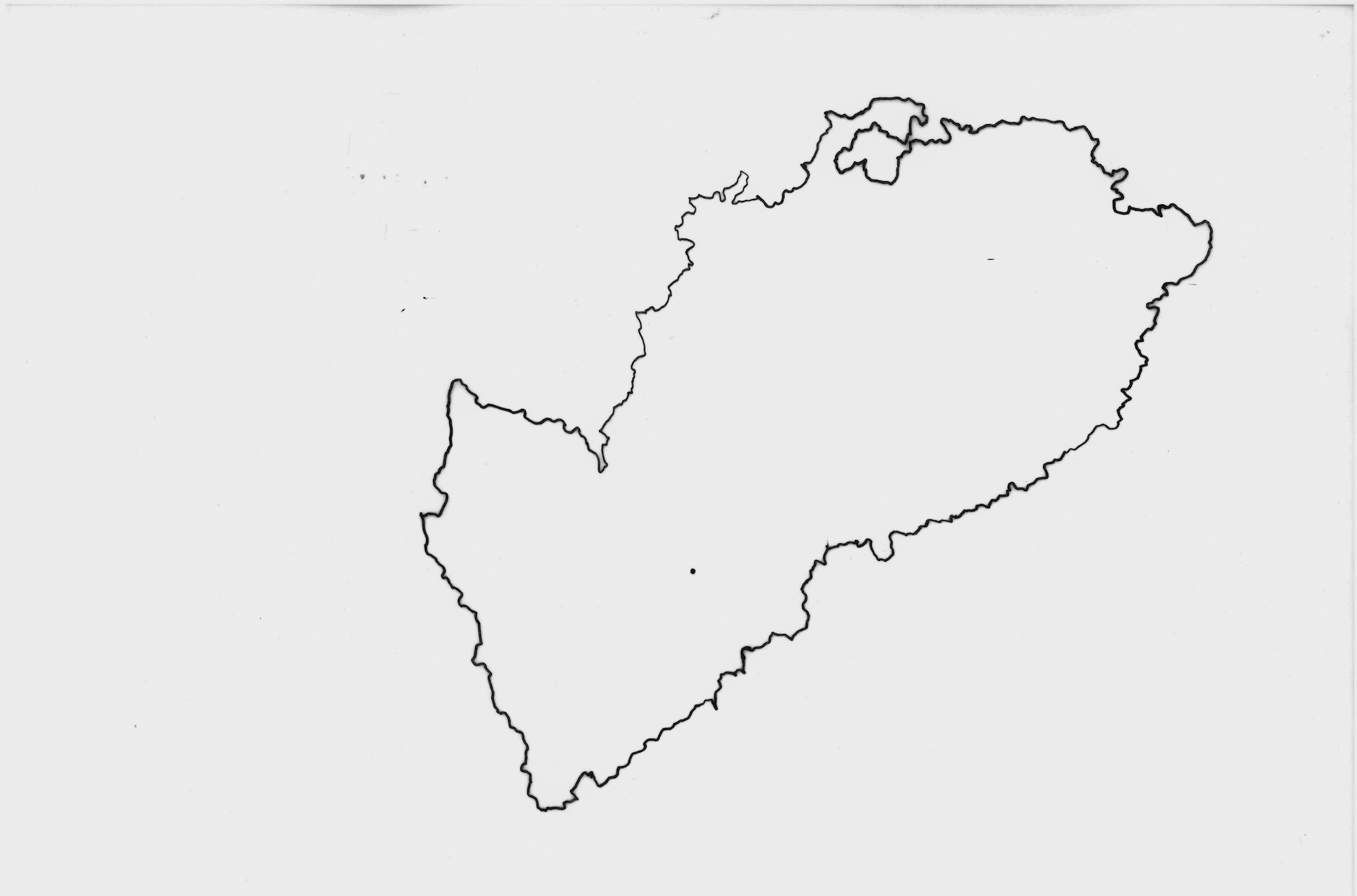

Let me introduce you to my method of locating where you belong when you feel you do not belong where you are.

What you will need:

– a pencil

– a sheet of tracing paper

– access to Google Maps (on any device, preferably desktop).

Instructions:

1. Think of a specific place you consider to be home. If there are multiple, or you couldn’t decide, select the first home you remember;

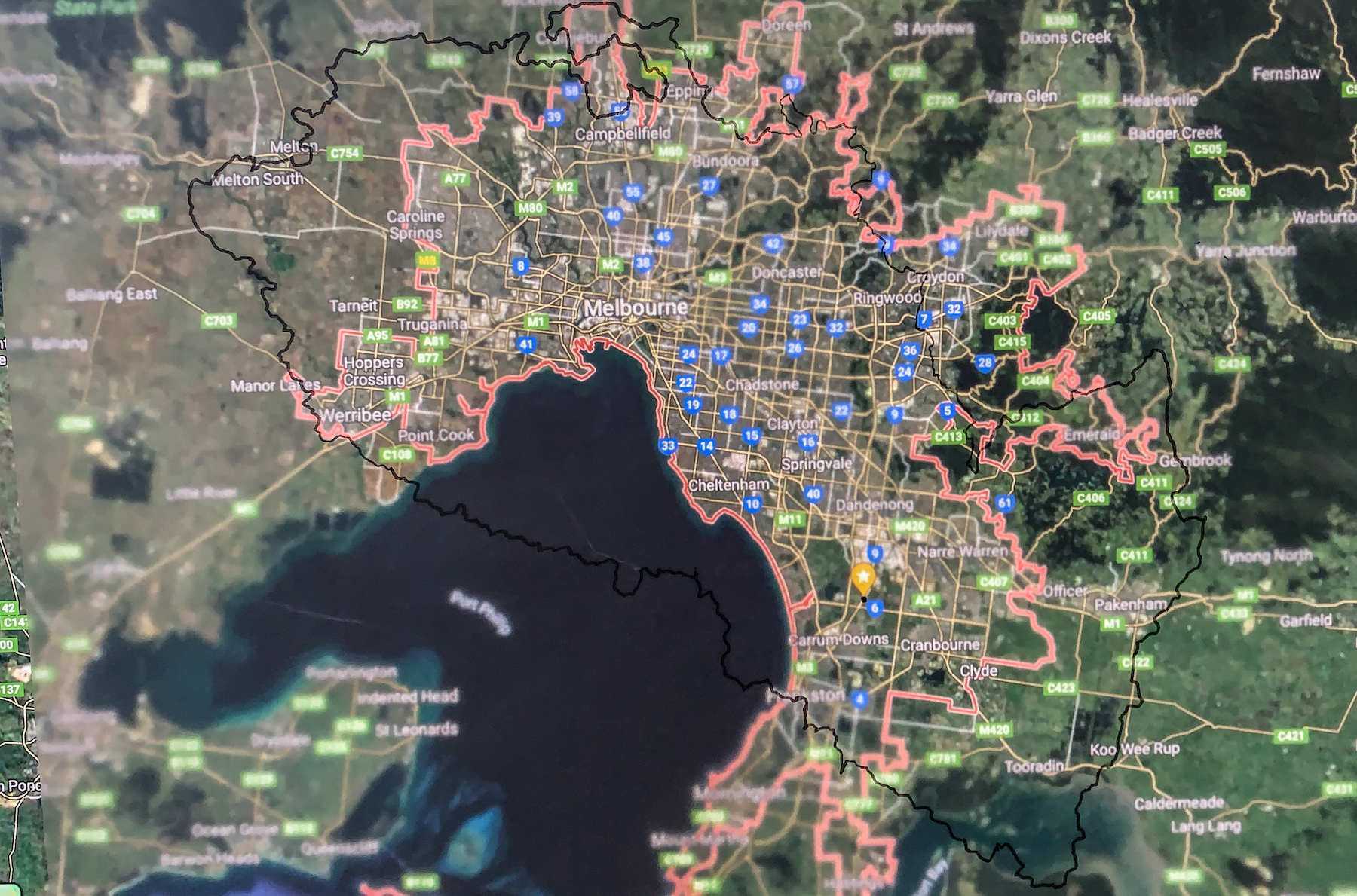

2. using Google Maps, locate your home and the border of the city where it sits;

3. place the tracing paper over the screen, trace the border of the city with your pencil to form a map;

4. pinpoint the specific location of your home.

5. Next, using Google Maps, search for the city you’re in right now, locate its border on the screen;

6. superimpose your tracing paper map onto the screen, zoom in or zoom out on Google Maps to align the borders of the two locations;

7. identify the corresponding location of your home in the city you are in now;

8. you have found your alternative belongingness.

As I might have said, I found out that my home was on a swamp.

Or my home is on a swamp? Tenses are confusing.

10

The fixation of holding on to somewhere immobile is determined by the fact that what’s already past is unchangeable and irretrievable. We inhabit the present and reminisce about the past—it’s impossible to step in the same river twice, yet we are still longing to trace back to that moment; you might see it as a common sensation of time in general. However, it is worth noticing that when I render home as a psychic object, even though it is a memory event … [that] belongs to lost time,⁵ I do not participate in nostalgia at all. I prefer to unfold it through an alternative view of time foregrounding time’s punctiform character rather than its stretched character.⁶ All those locales in the axis of time are only individual dots one after another.

Try to let go of the perception of a block of stretched time, consider memory events as several now points that happen simultaneously and only mark before and after. Think of the consequential impact each point enacts on us. For instance, I am scrutable to myself, before I left you; I cannot terminate my mourning, after you’re gone. The before-after perception grants us the freedom to assess those radical influences without the disorientation of reminiscence. Episodic memory is thus accessible to us as a surface imprinting a unique time and geographical location. It offsets the attempt to reinstate the long-lost time that reality-testing has proven irredeemable.

If I was always lost in being riveted by home as a crumbling representation from the past, this substitute viewpoint, then, finally empowers me to recognise and acknowledge how each encounter with home shapes and reshapes my identities.

11

That afternoon I was having a siesta in the shade under that gum tree, almost falling asleep surrounded by the spear grass, not knowing it would be gone very soon. I came back exactly one week later, only to find a plain field of grass roots exposed under the sun. For a second, I couldn’t distinguish which reality is real. I talked to a gardener who’s been working for different cemeteries for over a decade, and he said it is the first time they ever trimmed that field as the beginning of the government’s ten-year plan to expand the memorial park. He told me my home is nothing natural but built over a 12-foot layer of dirt. (Or did he say 12-meter? Memories are so unreliable.) He asked me do you know it used to be a swamp? I said I know, but I didn’t tell him that this is actually my home. In the end he shared with me his favourite spot—Springvale Cemetery. His reason is there’s no sadness of death, only celebration of life. But I think on that day I still secretly experienced five stages of grief.

I know I shouldn’t have. Spear grass is a vigorous plant.

12

The one named “stranger” will never really fit in, so it is said, joyfully. To be named and classified is to gain better acceptance, even when it is a question of fitting in a no-fit-in category. The feeling of imprisonment denotes here a mere subjection to strangeness as confinement. But the Home, as it is repeatedly reminded, is not a jail. … [U]nlearning strangeness as confinement becomes a way of assuming anew the predicament of deterritorialisation: it is both I and It that travel; the home is here, there, wherever one is led to in one’s movement. ⁷

13

I am/was here, but I am/was also there.

You see, I will always be a stranger, but I can at least be a stranger who lives in her own home. In other words, the negotiation of migratory melancholia sits in between mourning and melancholia: it is neither withdrawing from the loss, nor prolonging it, but to suspend the frustration of identification and the sentimentality of forfeiture—it is to fully introject estrangement into the ego, and say, I recognise my alterity, I refuse to renounce it, I defend to the death strangeness and otherness.

The incapacity for determining home finally dissolved within time’s passage. My desire fails in the way a dog chases its own tail. The futility of searching for home crashes over me, in the ashes I recognise my past, present and future; all those surfaces imbricate over each other, spreading upon me, through this vision I behold myself: I am wandering on a swamp, hungry and gloomy like a ghost.

Notes

1. László Krasznahorkai, The World Goes On (London: Tuskar Rock Press, 2018), p. 13.

2. Julia Kristeva, Black Sun: Depression and Melancholia, trans. Leon S. Roudiez (New York; Oxford: Columbia University Press, 2006), p. 61.

3. See Francis Rowland McGuire and City of Chelsea Historical Society, They Built a River : A Short History of the Carrum Swamp, Its People and Its Reclamation (Chelsea, Victoria: City of Chelsea Historical Society, 1979), p. 25; E. J. Lupson and Victoria. State Rivers Water Supply Commission, The Carrum Swamp Lands : History of the Carrum Waterworks Trust / by E.J. Lupson (Melbourne: State Rivers and Water Supply Commission, 1940); W. J. Mibus, Carrum Drainage District (Melbourne: State Rivers and Water Supply Commission, 1961).

4. William Bruton, Local History: Carrum to Cheltenham, 1999, p. 5.

5. Julia Kristeva, Black Sun: Depression and Melancholia, trans. Leon S. Roudiez (New York; Oxford: Columbia University Press, 2006), p. 62.

6. From Hegel to Nietzsche, there’s no escape from time’s duality. No matter punctiform or stretched, time is moving forward. Time’s punctiform character I’m addressing here, however, refers to the platonic tradition that views time as immobile. See Edith Wyschogrod, An Ethics of Remembering: History, Heterology, and the Nameless Others (The University of Chicago Press, 1998), p. 152.

7. Trinh T. Minh-ha, Elsewhere, within Here : Immigration, Refugeeism and the Boundary Event (London, UK: Routledge Taylor & Francis Group, 2011), p. 30.

Artist Statement

My Home is on a Swamp (A Practice of Belonging and Un-belong) My Home is a research-based project consists of mapmaking instructions, a personal essay, a performance documentation between my cousin and myself, and a live performance. This is also my own journey to comprehend a melancholic state that has long burdened me. I named it migratory melancholia, a psychological process of constructing and reclaiming home as an abstract and internalised representation that is beyond its physical and spatial properties.

I consider migratory melancholia to take place after migrating from an old home to a new home. Leaving her familiar surroundings, she is forced into the negotiation of a host of losses along with the assimilation process.¹ Her losses are indistinguishably both material and conceptual; her attempt to overcome the alienness is often thwarted. Unable to resolve or to be accepted, she conceptualises her lost home into a sense of unreachable belonging that she exerts to hold on to only in the imaginary and symbolic realms.

My Home is on a Swamp (A Practice of Belonging and Un-belong) begins with introducing a mapping method and performing on the site located under the instructions. It establishes certain rules that pin down the location of your proxy home in the present when you believe you belong to somewhere else from the past. This is not so much a fantasy to travel back in time/place as an experiment to view time/place differently—memory events in association with home are merely surfaces marked with time and geographical locations. These surfaces don’t reside in the long-lost past but coexist simultaneously at this very moment. I invite the viewer to experience the perception that prevents her from retrieving the past and includes her into the present. Through such perspective, I posit a substitute structure to penetrate the logic of migratory melancholia; which oscillates in-between the work of mourning and melancholia, allowing her to assimilate within given boundaries. She identifies the impact of detachment in order to fully recognise her own otherness; she refuses to devour such alterity, but to respect it and its resistance to disappear—she settles into the new home with the old home carried in her.

I must stress that my proposition can only be legitimised when recognising the history of (im-)migration, institutionalized discrimination, marginalisation and structural exploitation. It is critical to detect and reject the discourse that ascribes migration melancholia to cultural conflicts rather than political forces, or else my practice of belonging and un-belonging would counterproductively contribute to another form of social inequality—self-oppression.

This body of research-based work illustrates the parallel between my personal history and my encounter with the site. My research into the history of Carrum Carrum Swamp (where the site was located) and the tribal life of the Boonwurrung people living on the Mordialloc reserve in the late 19th century is indispensable to this project. Based on the historical records I could find in the State Library of Victoria, I realised it’s impossible to form a genuine or comprehensive understanding of the land’s history and the daily life of the Traditional Owners of that time The sources (both primary and second-handed) are extremely limited and biased, mostly written by white men from colonial perspectives aiming for reclamation and disappearance. Moreover, in those already inadequate records, there’s hardly anything that could give me insight into the tribal life of Indigenous women on the reserve—to learn their life stories—or even to know their names. I also want to acknowledge the problematic history of cartography itself. Just like in the written history, the embodied Indigenous knowledge is absent in mapping; such omission is a daily reminder of how colonial maps function as cartographic tools for annihilating Indigenous history.² If you’re in Australia, I invite you to extend on my instructions with the AIATSIS map of Indigenous Australia as a reference.³ I urge you to identify whose land you’re on, and to learn which Aboriginal or Torres Strait Islander Country, language group or community holds your belongingness.

Research for this project is an ongoing process of reflecting on my own positionality—I have no access to another’s life story;⁴ I am no historian or anthropologist, either; nevertheless, what I can do is connect the land with my body, remap through my body, and introspect: when the past is destined to be unreachable and unrecoverable, how do we exercise remembrance of the nameless and the voiceless? In front of human cruelty, what words can art utter, and in what place does art stand?

Notes

1. Inspired by and responding to American philosopher Edith Wyschogrod’s vision of heterological historian—[she] is better able to speak for the other if alterity is disclosed in the feminine gender…, I propose that a migrant’s pronouns are she/her/her, which will be used throughout this work. It’s more attainable for her to live with her own otherness when she approaches it in the third-person feminine pronounces. See Edith Wyschogrod, An Ethics of Remembering: History, Heterology, and the Nameless Others (The University of Chicago Press, 1998), p. xiii.

2. See Matthew Sparke, “Mapped Bodies and Disembodied Maps: (Dis)placing Cartographic Struggle in Colonial Canada”, in Places Through the Body, eds. Heidi J. Nast and Steve Pile (New York: Routledge, 1998), pp. 305-36.

3. See Map of Indigenous Australia, https://aiatsis.gov.au/explore/map-indigenous-australia.

4. Who has access to whose cultural heritages? —a central question in understanding and supporting the self-determination and sovereignty of Indigenous peoples all over the world. See Donna Haraway, “It Matters What Stories Tell Stories; It Matters Whose Stories Tell Stories,” a/b: Auto/Biography Studies, 34:3, 2019, pp. 565-75, DOI: 10.1080/08989575.2019.1664163.

Cristea Nian Zhao comes from a background in film. She has written and directed several narrative short films and documentaries. Since immigrating to Australia in 2018, her practice has expanded into performance, video installation and text-based work. Language, spoken narrative and shared listening are crucial to her practice. Her interest is in unearthing various forms of loss from personal history and collective memory. The possibility/impossibility of mourning and reconciliation frequently lies beneath her works. Zhao recently graduated from RMIT with a Masters in Fine Arts.

cristeazhao.com

All images courtesy of the artist, Cristea Nian Zhao.

My Home is on a Swamp (A Practice of Belonging and Un-belonging), 2021-2022.

Xiaowen Zhang, Wandering in L. city, 03.04.2021. Cristea Nian Zhao, Wandering in M. city, 01.02.2022

Performance documentation, 2021-2022, Single-channel video, 6:15.

For a copy of this essay direct from the artist, Cristea Nian Zhao, please fill in the following form.